Burgers, Behaviors and Backwards Thinking

Investment ManagementApr 25, 2024

In this week’s article, we will be revisiting the thoughts and words of others to help make some important points all investors should keep top of mind when it comes to long-term investing. We’ll start first with Warren Buffett’s 1997 letter to shareholders. In this letter, the notorious hamburger fanatic asked a straightforward question:

“If you plan to eat hamburgers throughout your life and are not a cattle producer, should you wish for higher or lower prices for beef? Likewise, if you are going to buy a car from time to time but are not an auto manufacturer, should you prefer higher or lower car prices? These questions, of course, answer themselves”.

He then goes on to build on this thought exercise and makes a point that would appear to be completely backwards:

“If you expect to be a net saver during the next five years, should you hope for a higher or lower stock market during that period? Many investors get this one wrong. Even though they are going to be net buyers of stocks for many years to come, they are elated when stock prices rise and depressed when they fall. In effect, they rejoice because prices have risen for the “hamburgers” they will soon be buying”.

Jason Zweig of the Wall Street Journal recently made a very similar “backwards” point when he wrote:

“I like to say that the problem with stocks is that they contain the letter T. If they were called socks instead, people would treat a 20% decline in price not as a selloff but as a sale. When socks get 20% cheaper, you don’t rush to get rid of the ones you already own; you check your sock drawer to see if you need a few more pairs. Young investors should treat stocks the same way.“

In short, the point both are making here is that as consumers, we would obviously prefer lower prices of things we are buying regularly, whether it be hamburgers, cars, or socks. Buy low, sell high seems intuitive right? However, when it comes to buying stocks and other financial assets, most people think the opposite way. We are conditioned based on the anxiety we feel seeing prices fall as we check our portfolios, the financial media’s coverage when the market is down, and the general feeling of uncertainty about if it is ever going to end. It feels better to see the prices of financial assets go up, even if we know we are going to be net buyers of these assets in the next 1, 5, or 10 plus years. Now that is a little backwards. Why is it like this?

Our instincts as human-beings, the same ones that allowed our ancestors to survive and avoid danger in all kinds of environments for thousands of years, make us lousy investors. Scott Nations is the author of a book The Anxious Investor, which focuses on how important this concept is. We tend to think of investing as a science, but at the end of the day it is done by people. People who are biased, emotional, and hardwired with thousands of years of fight or flight biology. We can’t remove these things, but we can be aware of them to make better decisions. Nations goes on to say:

“None of the behavioral biases that humans display when investing—not a single one—generates better returns or minimizes risk…Learning about, understanding, and accounting for your own behavioral quirks can do more to improve your long-term investing results than even a roaring bull market can.”

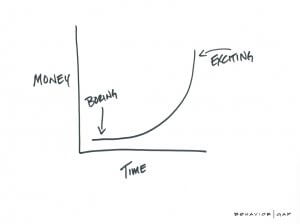

In Ben Carlson’s book, A Wealth of Common Sense, he expands on this thought with another backwards sounding concept- it is not the raging bull markets upward that build wealth, it is actually our decisions during the downturns that dictate our outcomes:

“Over decade-long time horizons, your investment performance will mainly be derived from how you handle corrections, bear markets, and market crashes. During every single bear market there will be times when you wonder if the losses will ever stop. You will always wonder how much lower the market can go. The economic news will be terrible. Other investors around you will be depressed. Pessimism becomes pervasive.“

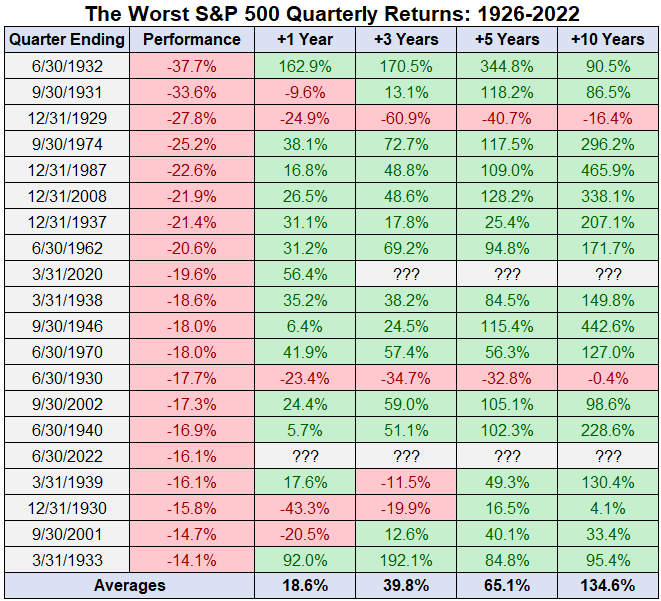

If you look at history, this concept is backed up by the numbers. The market generally follows up extreme downturns with very positive returns in the years ahead (apart from the Great Depression):

In other words, human emotions can lead us to buy and sell at the exact opposite moments that we should. To be clear, there is a reason every investment advertisement contains the following statement: “past performance is not indicative of future results”. No one knows what the future will hold, and our goal here is not to predict what will happen next. Rather, it is to provide historical context.

Importantly, none of this is to say that what happens during market sell-offs is not scary or incredibly serious. We are constantly reminded that the world feels more uncertain with each passing day. If I am approaching retirement, I don’t really care about hamburger analogies, charts, or context. I want to be sure I can retire comfortably and enjoy life as I had planned. However, all these facts only reinforce the importance of good planning. A good plan shouldn’t hinge on 6 months or a year of market performance, but rather focus on what can be controlled to allow investors to weather the storm and avoid mistakes. We’ll use one more thought, this one from writer Morgan Housel, to help bring our theme of backwards thinking home: What you do 99% of the time won’t matter that much if you make a big mistake 1% of the time.

“The investment decisions you make on 99% of days don’t matter. It’s the decisions you make on a small number of days when something big is happening – a massive downturn, a frothy market, a speculative bubble, etc. – that make all the difference.“

Citations

Chairman’s Letter, Warren Buffett- Berkshire Hathaway, 1997

The Intelligent Investor- Of Crashes and Fees, Jason Zweig- Wall Street Journal, July 12, 2022

The Anxious Investor: Mastering the Mental Game of Investing, Scott Nations, April 2022

On the Inevitability of Bear Markets, A Wealth of Common Sense, Ben Carlson, July 6 2022

The Psychology of Money, Morgan Housel, 2020