The Notorious A.M.G.

Financial PlanningFeb 27, 2025

Chances are you’ve never heard of Sir David Brailsford. He’s the former head of the British Cycling Team who transformed Great Britain’s cycling program from an afterthought into a record-setting powerhouse. When he took over in 2002, the team had won just a single gold medal in 76 years. By the 2008 Beijing Games, they captured 7 out of 10 possible golds—and then did it again in London four years later.

His secret? A concept he called the aggregation of marginal gains. For simplicity purposes, and to help our article title make sense, we’ll just call it the A.M.G.

What is the A.M.G.?

It starts with an idea that seems counterintuitive for anyone feeling far away from their goals: think small, not big.

Brailsford, a former professional cyclist with an MBA, came across a famous business school case study on Toyota’s success. The company’s advantage came from kaizen, a Japanese principle meaning “continuous improvement”. Inspired by this, he applied the same philosophy to his cycling team. Once they identified the core factors that drove success, they focused on improving every small detail of their process.

Nothing was overlooked. They optimized aerodynamics in a wind tunnel, developed better ways to remove dust that could affect bike maintenance, and even learned proper hand-washing techniques to prevent illness before races. They went so far as to transport their own mattresses and pillows to competitions to maximize recovery.

On their own, none of these changes seemed significant. In fact, some might even sound ridiculous for an Olympic team. But together, they made a huge impact. Over time, these small improvements compounded, leading to extraordinary results.

Everything Compounds—For Better or Worse

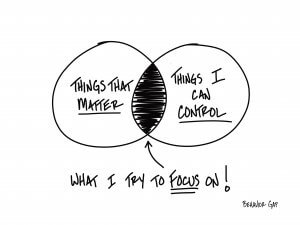

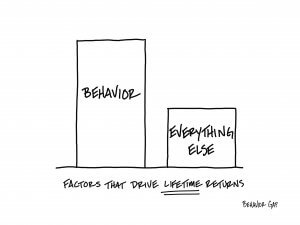

The power of compounding applies to everything—whether it’s cycling, manufacturing, or building wealth. If you stack small improvements in behaviors and processes on top of each other over time, the results can be massive.

Unfortunately, compounding works both ways. Good habits build momentum, but bad ones do too. Benjamin Franklin summed it up well: “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” The longer we do something inefficiently, the worse the long-term effect. This applies to every area of life.

Morgan Housel ties this back to wealth building in his book The Psychology of Money:

“Think about this in the context of how much time and effort goes into achieving 0.1% of annual investment outperformance—millions of hours of research, tens of billions of dollars… when there are two or three full percentage points of lifestyle bloat that can be exploited with less effort.”

If we can consistently improve a process that helps us spend less than we earn and invest the difference in a way that outpaces inflation, we are almost guaranteed to become financially independent over time.

The “Notorious A.M.G.” and Wealth Building

The best way to build wealth is a lot like how Brailsford built a dominant cycling program—through the aggregation of marginal gains. A good financial plan isn’t about chasing shortcuts; it’s about setting a solid foundation and making ongoing adjustments based on your psychology and evolving circumstances.

This approach is too boring for most people. That’s why we are calling it the Notorious A.M.G.—because most people don’t want to do it. There’s a reason Americans spend more on lottery tickets than on movies, video games, music, sporting events, and books combined. We crave the next big thing that promises quick success, even though there’s a proven, reliable way to get there with patience and discipline.

Hungarian stockbroker André Kostolany put it best:

“I can’t tell you how to get rich quickly. I can only tell you how to get poor quickly: by trying to get rich quickly.”

Citations

How 1% Performance Improvements Led to Olympic Gold, Eben Harrell- Harvard Business Review, October 30, 2015

Richer, Wiser, Happier, William Green, 2021

The Psychology of Money, Morgan Housel, 2020

Want to Get Rich Quick? Who Can Stop You?, Jason Zweig- Wall Street Journal, May 7, 2021