When Leverage Failed

Investment ManagementApr 02, 2021

Roger Lowenstein’s book When Genius Failed is one of the most fascinating financial books ever written. It tells the inside story of Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM), a leading hedge fund whose employees included Nobel Prize winning economists, world renowned mathematicians, and other experts from academia and Wall Street that imploded in spectacular fashion in 1998.

It is a well-written account of a group of investors who believed they had constructed a strategy that completely removed risk while allowing for outsized gains. Spoiler alert: it did not work out well. When the market moved in the other direction from the positions they owned, not only did the hedge fund collapse, but it almost jeopardized the entire financial system’s stability. A group of big banks bailed them out, which prevented a worst case scenario. How is it possible one hedge fund could have such an outsized impact? The answer lies in one very important word: leverage. Before its collapse, it is estimated that Long-Term Capital Management had only about $5 billion in assets under management, however due to the leverage and instruments called derivatives it used, it controlled over $100 billion and had invested positions worth over $1 trillion. Yikes.

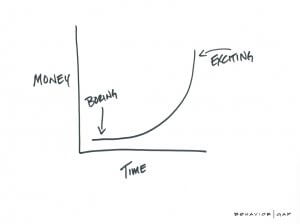

The Oxford dictionary describes leverage when it comes to investing as: “using borrowed capital for (an investment), expecting the profits made to be greater than the interest payable”. In other words, leverage is a fancy word for investing with borrowed money. If you make more money than the cost of borrowing it, your returns are much higher than they would have been using only your own capital. Here is a simple example: Let’s say you want to buy $10,000 in stock, but you only have $5,000 in cash. Leverage allows you to buy the full $10,000 while only using the $5,000 on hand. The rest is bought using money that is loaned to you (this is called “on margin”). You are able to multiply your gains and risk less up front. The only problem is gains aren’t the only thing that are magnified. So are losses. If things go bad quickly, the bank or trading platform who lent you the money can ask you to put up what you owe or sell your positions at a steep loss. If you think this sounds a bit like what a loan shark does, you aren’t very far off. While When Genius Failed is a fascinating story, it was also nothing new at its core. The book could easily be retitled When Leverage Failed and become a series with more parts than Harry Potter.

This week a similar situation unfolded, thankfully with less risk to the broader market and financial system. A little-known family office (a hedge fund that invests only one wealthy family’s money) called Archegos Capital Management was using huge amounts of leverage, and then the investments it owned moved in the wrong direction. Reports estimate the fund may have borrowed as many as $5 or $10 for every $1 dollar of its own money invested. They were also using complex investment instruments called derivatives to make it easier to have even more exposure to various stocks. Bloomberg’s John Authers summarizes both this and the LTCM situation at the same time: “A fund had more exposure than people realized, because it had more leverage than they realized. When the trades went wrong, it had no choice but to sell, forcing down those securities, and threatening the banks that had lent them money.” Shares of the stock positions the family office owned all declined dramatically as they were sold, as did the stock prices of the banks who lent the money, creating a domino effect. The banks involved and regulators are investigating how this was possible. Keep an eye out for the book that will be written on this one too.

When you zoom out from each story, the principal factors that caused each situation were not much different than what kicked off the Global Financial Crisis either. Authers described the story of Long-Term Capital as “a dress rehearsal for the Global Financial Crisis” a decade later. He’s right. Banks were leveraged to the hilt, and invested in complex and hard to understand products related to mortgages. The individuals taking out mortgages they could not afford were also over-leveraged. When housing prices declined and access to capital dried up, things got ugly in a hurry. Leverage can be a useful tool, but history shows it is also one that breeds moral hazard and reckless behavior. Greed and leverage often go hand in hand. Each situation at its core boils down to the same human behavior that has been around forever: wanting something for nothing. It is the root cause of many major fiscal problems.

Leverage just means achieving results greater than what you put in. It doesn’t eliminate risk though; it just passes the hot potato to someone else. It’s like a teenager heading to college with their parent’s credit card and no rules. While the risk to the teenager (investor) may be limited, the risk to the overall household (system) increases. This type of behavior is not unusual when access to money is cheap and easy like it is today. The question is if this is a one-off or a sign of other underlying issues to come.

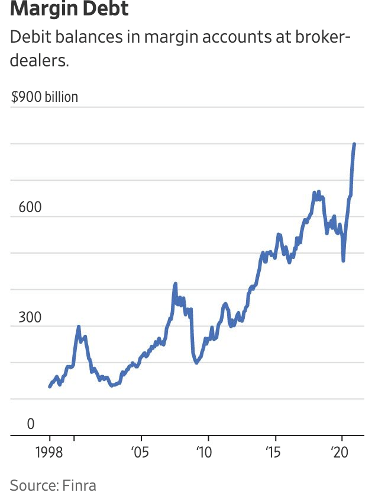

A combination of ultra-low interest rate policy by the Fed, technology platforms making it easier to borrow and trade, and government stimulus checks has led to margin debt outstanding of $799 billion in January compared to $562 billion a year earlier. It is these conditions that also helped cause the Game Stop situation. Individual investors borrowed heavily to pile into the stock pushing it higher and higher. This is why Robin Hood had to halt trading at one point, because too much of the buying was being done on margin.

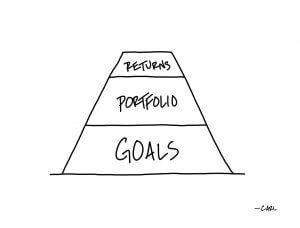

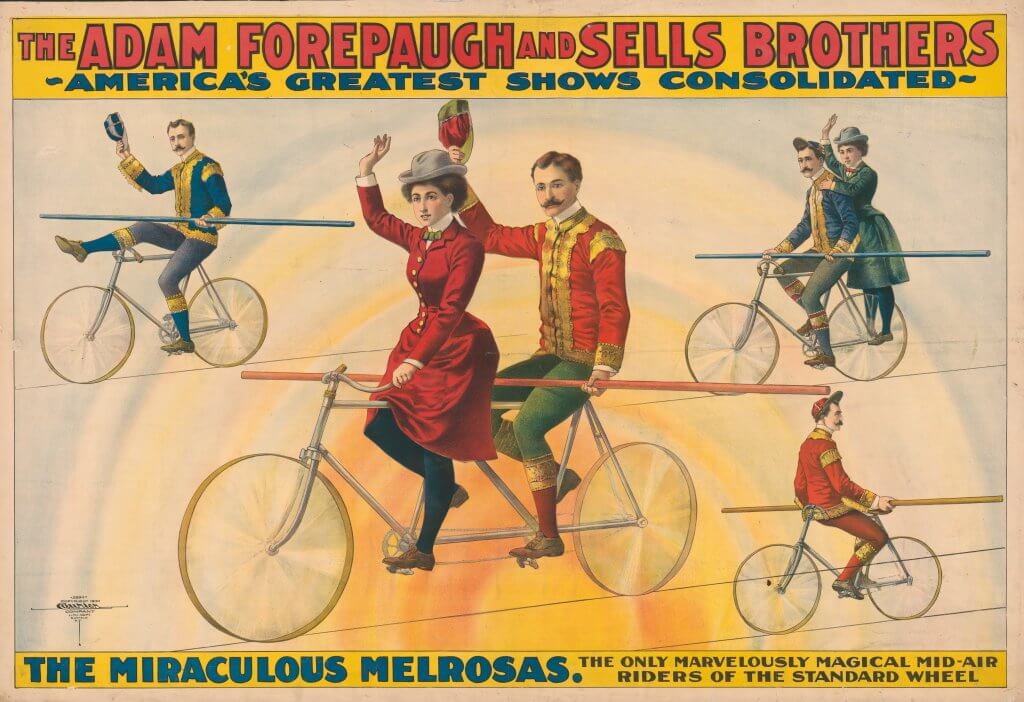

Whether it’s a sophisticated investor, a company, or a household’s balance sheet, the same principals apply when it come to the risks of leverage. Borrowing money to buy assets can work for a while, especially when the value of what you are buying keeps going up. However, as we saw with LTCM, The Global Financial Crisis, Game Stop, and now Archegos, the more leverage there is, the less room for error you have. Relying on debt to get you bigger returns, better quarterly earnings, or a bigger house erodes your margin of safety when conditions change. It is the investing equivalent of trapeze artists swinging around without a safety net. It could make for a heck of a high-flying show and work out just fine, but not much has to go wrong for it to end badly.

Citations

When Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Long-Term Capital Management, Roger Lowenstein, 2000

What to Know About the Margin Calls Roiling the Market, Nicholas Jasinski- Barron’s, March 29, 2021

Credit Suisse, Nomura Slump as Banks Tally Archegos Damage, Takashi Nakamichi, Cathy Chan, and Sridhar Natarajan- Bloomberg, March 29, 2021

Derivatives Don’t Cause Market Crises, People Do, John Authers- Bloomberg, March 30, 2021